By Nikos Mantzaris, Senior Policy Analyst, The Green Tank, Greece & Member of the Greek National Committee for Climate Change

Abstract

The four Institutions involved in Greece’s economic rescue programs, insisted on the partial privatization of Public Power Corporation’s (PPC) lignite portfolio based on a case that was initiated 20 years ago when the economic realities of lignite were vastly different. This paper criticizes the European Commission on its persistence to enforce such one-dimensional approaches, while contradicting even the EU’s own climate policies. It further highlights the role of environmental NGOs and think tanks, which, together with key developments in EU legislation prevented a structural lock-in to lignite and paved the way for the decision to phase out lignite by 2028.

1. Introduction

In 2019, Greece became the first member state of the European Union (EU) utilizing lignite (brown coal) for electricity production to announce that it would phase out lignite prior to 2030 (Mitsotakis, 2019). However, this decision and the actual decline of lignite use in Greece recorded in recent years, were far from guaranteed, due to conflicting factors influencing the evolution of Greece’s energy policy. On the one hand, developments in EU’s climate and energy policy combined with the advocacy efforts by environmental NGOs and thinks tanks in Greece and the EU were contributing towards the decline of lignite use. On the other hand, EU’s policy associated with Greece’s economic rescue program and the failure of Greece’s political leaders to appreciate the dead-end for coal in Europe, were effectively pushing in the opposite direction, towards the prolongation of the lignite-based electricity model.

In the following, we will present and analyze the complex interplay between these contradicting factors. Three key EU policy developments which contributed to a decrease in lignite use in Greece will be presented first, followed by a discussion on the Greek Public Power Corporation’s (PPC) antitrust case aiming at providing access to Greece’s lignite deposits to companies other than PPC. Emphasis will be placed on the persistence of the Institutions responsible for Greece’s economic rescue program (the European Commission, the European Central Bank, the European Stability Mechanism, and the International Monetary Fund) to enforce the decision on the antitrust case, years after the case was first brought to the European Courts, at a time when lignite economics had drastically deteriorated. Throughout the analysis of these different policy and legal facets, the positions and specific actions of environmental non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and think tanks in Greece and the EU will be presented and discussed. We conclude with a critical assessment of Greece’s case which could help policy and decision makers avoid similar threatening situations in the future.

2. The role of lignite in Greece

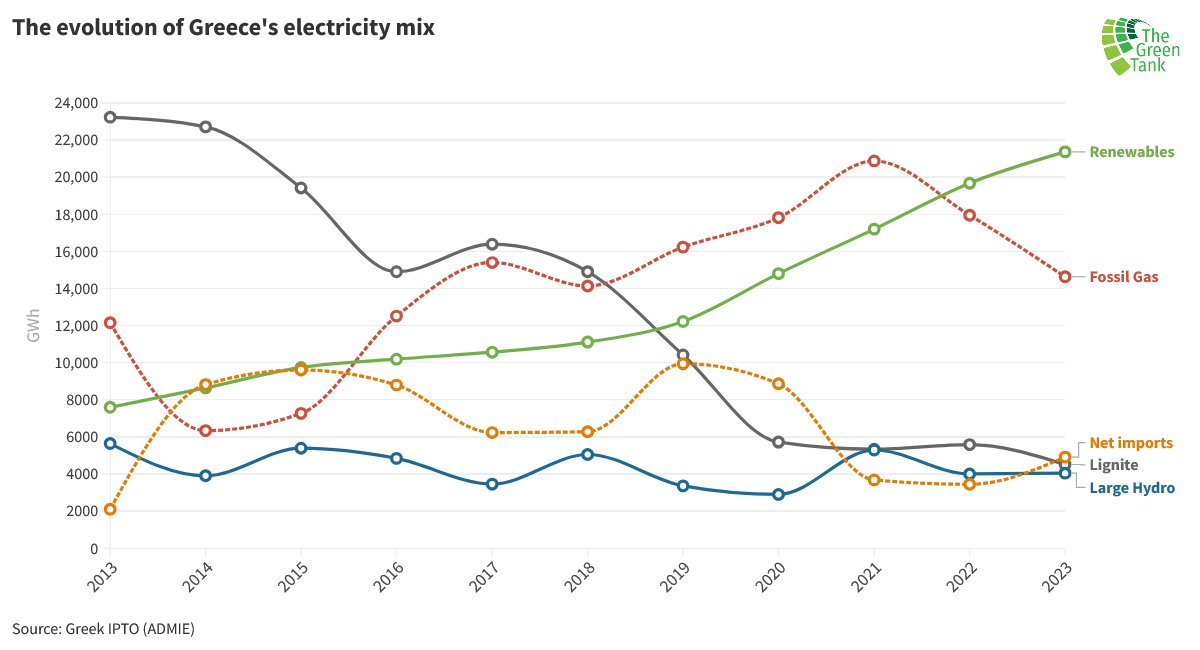

Lignite has been the dominant fuel in Greece’s electricity mix since the 1950s. Lignite extraction and combustion to produce electricity is exclusively controlled by the Public Power Corporation (PPC), Greece’s largest company. The share of lignite in covering electricity demand reached as high as 78% in 1993 (Vassos &Vlachou, 1997). Since 2013, however, it started to decline and in 2019 surrendered for the first time the top spot in Greece’s electricity mix to fossil gas, which retained it for three consecutive years, before losing it to renewables in 2022 (Figure 1). That same year lignite covered just 11% of demand, producing 5.58 TWh, one fifth of its output ten years ago and a mere 0.24 TWh more than its up until then historic low recorded in 2021 (5.34 TWh). In 2023, due to the acceleration in the deployment of renewables, a new historic low was recorded for lignite (4.51 ΤWh), which was also accompanied by a drop of fossil gas-based electricity generation back to 2018 levels.

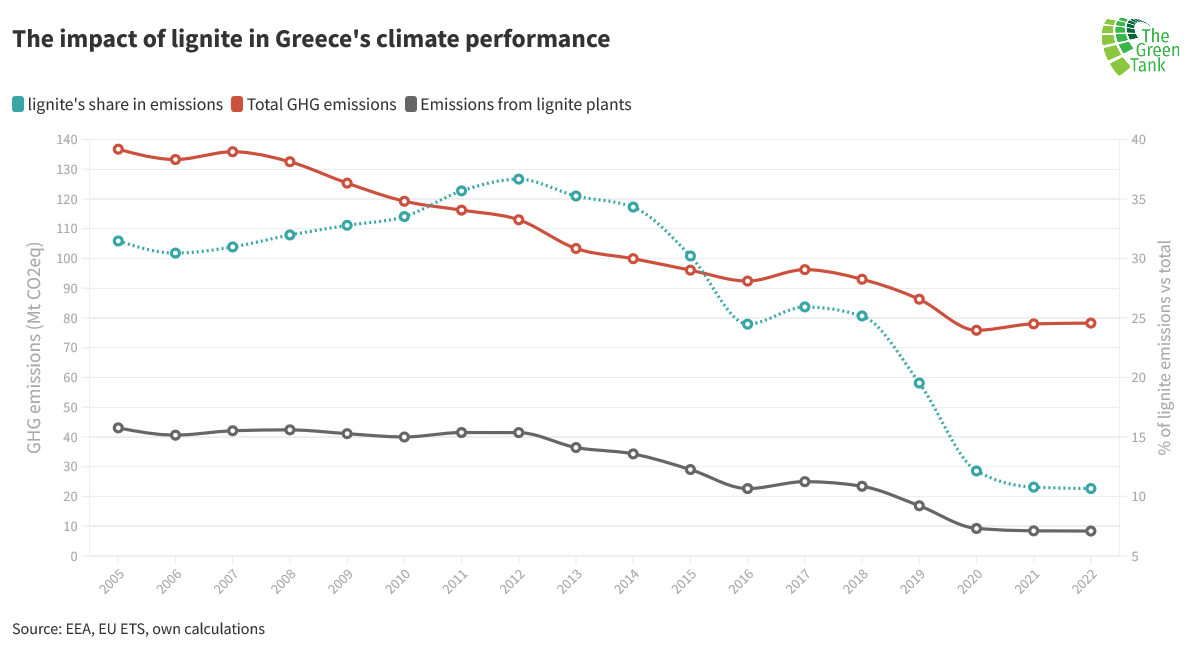

Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from lignite plants contributed the most in Greece’s total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions throughout the years. Since the EU’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) began to operate in 2005 and cumulatively, until the end of its third phase in 2020, emissions from Greece’s lignite plants accounted for over 30% of the country’s overall GHG emissions, one of the largest such shares in the EU. Hence, the recently (after 2019) accelerated drop of lignite use and its substitution by renewables and the less polluting fossil gas, has benefited Greece’s climate performance profoundly. Lignite’s share in the total GHG emissions dropped to 10.7% in 2022 (Figure 2) from 31.5% in 2005. That same year Greece recorded a 28.4% decrease in net GHG emissions compared to 1990 levels, four percent below the EU average (-32.5%), whereas in the past Greece had been consistently one of the laggards in the EU with respect to its climate performance.

3. European Policy Developments

The 2015 Paris Agreement was a turning point in international climate policy. Although the phase out of fossil fuels was not explicitly mentioned in the agreement’s text (United Nations, 2015), the focus on limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5oC and the introduction of the climate neutrality goal, were enough to mobilize the EU. Limiting the use of coal, the most polluting of all fossil fuels, became a priority in the EU’s climate and energy policy. The revision of three major EU files after the Paris Agreement can be considered as milestones: the EU ETS Directive (European Parliament & the Council, 2018), the new Best Available Techniques conclusions (BATc) (European Commission, 2017) associated with the EU Industrial Emissions Directive (IED) (European Parliament & the Council, 2010) and the recast Electricity Market Regulation (EMR) (European Parliament & the Council, 2019).

3.1. The EU Emissions Trading System

The carbon price directly burdens the operating costs of lignite plants. Its value, which is the cost for purchasing a single emission allowance equivalent to one tonne of CO2, is largely determined by the rules set in the EU ETS directive. The 2015-2018 revision of this Directive led to an explosion of the carbon prices starting in the second half of 2018, which in turn had a profound impact on the economics of the coal industry across the EU.

Specifically, it was during this revision that the EU agreed on a higher climate ambition for the fourth EU ETS phase (2021-2030) and an emissions reduction target of 43% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels (European Parliament & the Council, 2018). More importantly, the EU established the so-called “Market Stability Reserve” (European Parliament & the Council, 2015), a mechanism of removing excess emission allowances from the carbon market, thus stimulating the price signal through reducing their availability. As a result of these changes, the carbon price, which was hovering around 4-8.5 €/t between 2013 and early 2018, skyrocketed to 25 €/t by the end of 2019, surpassed 33 €/t in 2020 and more than doubled in 2021 to reach the 70 €/t milestone for the first time. The Greek lignite industry was hit more profoundly than the rest of the EU, since Greek lignite plants emit more CO2 per unit of electricity produced compared to plants in other member states. Therefore, Greek lignite plants are more vulnerable to high carbon prices.

Instead of realizing the financial catastrophe that was ensuing for the Greek lignite industry, PPC, the owner of all lignite assets in Greece, tried to bypass them. Throughout the revision negotiations, PPC actively sought to obtain a derogation of Article 10c in the EU ETS Directive, which would offer free emission allowances to its lignite plants. The overwhelming majority of Greek Members of the European Parliament (MEP) from all political groups supported this position in all committees as well as in the plenary of the European Parliament (European Parliament, 2017). The same was also true for the Greek government up until the final vote in the EP plenary in February 2017, after which it abandoned this quest in the Council and focused only on rendering Greece eligible for access to a newly formed ETS fund, namely the Modernisation Fund (Famellos, 2017). In addition, Greece advocated in favor of rendering retrofits of lignite plants eligible for funding from the Modernisation Fund, a position that was reflected in the Council’s general approach (Environment Council, 2017).

Environmental NGOs in Greece and the EU were also actively engaged in the legislative process, fiercely opposing both efforts. They argued that if Greece were granted the derogation, then a huge share of public revenue from the auctioning of these allowances would be lost on a polluting industry, when it could be used to support the shift of Greece’s energy model towards energy efficiency and clean energy as well as the Just Transition of Greece’s lignite regions (Mantzaris, 2017). They also brought to light that these free emission allowances were essential for PPC to build two new lignite plants (Ptolemaida 5 and Meliti 2) (Neslen, 2016). By highlighting the public admission of PPC’s CEO at the time that the two new lignite plants would not be economically viable without these free emission allowances (Panagiotakis, 2016), they further explained to decision makers in Brussels that PPC’s plan contradicts the very scope and spirit of the EU ETS Directive.

In addition, environmental NGOs advocated against the use of the newly established Modernisation Fund for retrofits of hard coal and lignite plants. They argued that the limited amount of funds available for the modernization of the energy systems in the eligible financially weaker member states should be used for developing clean energy infrastructure, instead of investing to prolong coal plants’ lifetime. At a time when the financially stronger member states were massively turning to renewables, rendering the coal industry in the financially weaker member states eligible for funding from the Modernisation Fund would widen the energy policy gap within the EU.

In the end, the eligibility criteria for obtaining an Article 10c derogation, remained as in the original EC proposal: only member states with a GDP per capita below 60% of the EU average in 2013 could make use of this derogation (European Parliament & the Council, 2018). Since Greece was above this threshold, it was not eligible to use part of the public revenue from ETS auctioning to subsidize the operation of its lignite plants. Moreover, EU decision makers excluded all investments in solid fossil fuel infrastructure from the Modernisation Fund, except for Combined Heat and Power (CHP) plants in Bulgaria and Romania.

Hence, the conclusion of the EU ETS reform in late 2017 meant that the Greek lignite industry would neither have free emission allowances to subsidize the operation of its lignite plants nor any funds to finance the expensive retrofits that Greek plants needed to undergo to comply with the IED and the accompanying BATc, which were also under revision.

3.2. The Best Available Techniques conclusions (BATc)

While the EU ETS Directive was being reformed, the process of updating the emission limit values for pollutants emitted by large combustion plants (sulfur dioxide, nitric oxides, dust, heavy metals etc.) was also approaching its conclusion. According to the IED (European Parliament & the Council, 2010), large combustion plants, including coal plants, would have to implement abatement techniques to comply with the new emission limit values set in the so-called “Best Available Techniques conclusions” (BATc) (European Commission, 2017), at the latest four years after the formal adoption of the corresponding document.

As the vote for the BATc was approaching, negotiations on the EU ETS Directive were tilting towards excluding funding for coal plant retrofits through the Modernisation Fund. Thus, the financial impact of the upcoming BATc vote would be even more profound. Environmental NGOs from Greece and the EU were actively advocating in favor of adopting the BATc with the stricter emission limit values. Their arguments were based on the well-documented environmental and health costs associated with the severe air pollution stemming from the operation of the lignite plants (EEB et al. 2016). On the contrary, the severe impact that the adoption of the document would have on the economics of coal plants across the EU led almost all coal producing member states to vote against it in April 2017. Greece was the only exception as it voted in favor of the BATc. The Greek government’s vote was a result of the gradual realization that there was no future in Greece’s lignite industry and coincided with the abovementioned failure to obtain free emission allowances for Greece’s lignite plants in the EU ETS Directive revision. With a share of the vote of 2.11%, Greece’s positive vote was essential to barely lift the overall majority 0.14% above the 65% threshold, required for approval (European Council, 2017) and lead to its adoption (European Commission, 2017).

As a result, Greek lignite plants would have to undergo expensive retrofits to comply with the new emission limit values, at the latest, four years after the official publication of BATc without, however, any form of state aid or funding from the Modernisation Fund.

3.3. The Electricity Market Regulation

At the same time as the above developments, the Electricity Market Regulation was also being revised as part of the EU’s “Clean Energy for all Europeans” package. Among other issues, the EMR regulates subsidies to power plants through their participation in the so-called “capacity mechanisms”. From 1998 until 2018, these mechanisms had subsidized coal plants with approximately €39 billion paid by electricity consumers across the EU (Mang, 2018).

With its 2016 proposal for a revision of the EMR, the EC was determined to terminate subsidies towards coal and lignite plants through capacity mechanisms (European Commission, 2016). The EC set an emission performance standard of 550 gr CO2/KWh as an eligibility criterion for plants to participate in capacity mechanisms. This standard effectively excluded all hard coal and lignite power plants.

During the negotiations Greece joined forces with Poland and managed to persuade the Council to adopt a drastically different position ahead of the trilogue negotiations (Verroiopoulos, 2017). Specifically, the Council’s general approach proposed amending the EC’s original proposal to: a) prolong the period during which existing plants could be subsidized through capacity mechanisms until 2035 and b) render new lignite plants, such as PPC’s new lignite plant “Ptolemaida 5”, eligible for participation in capacity mechanisms (Council of the European Union, 2017).

On the other hand, environmental NGOs in Greece and the EU strongly supported the original proposal by the EC to exclude all coal plants from capacity mechanisms (CAN, 2017) and advocated in favor of this position throughout the negotiations (Flisowska, 2018).

In the end, the recast EMR provided that no new coal plant could participate in any capacity mechanism and no existing coal plant could receive subsidies through a capacity mechanism beyond June 2025 (European Parliament & the Council, 2019). However, the agreement on the recast EMR contained a loophole: plants emitting above the 550 gr CO2/KWh threshold (i.e., coal plants) could receive capacity payments, provided they participated in capacity mechanisms that were approved prior to the day the Regulation came into force (July 4, 2019), and the corresponding contracts were signed before the end of 2019. This “grandfathering” clause left a window of opportunity for the Greek lignite industry to subsidize existing lignite plants through capacity mechanisms beyond 2025, as well as the new plant “Ptolemaida 5”, provided Greece had a capacity mechanism in place before July 4, 2019.

4. The antitrust case

The three abovementioned post-Paris Agreement developments in EU climate and energy policy were clearly signaling against the prolongation of the coal-based electricity model across the EU. However, for Greece, these were not the only signals received. A long-standing anti-trust case against the PPC’s monopoly in the exploitation of lignite threatened to keep Greece locked-in to lignite for the foreseeable future. This threat was in full display in the draft National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) the Greek government submitted for public consultation in November 2018 (Ministry of Environment and Energy, 2018), that is at the end of the negotiations of the ETS, BATCs and EMR. Therein, the participation of lignite in Greece’s electricity mix was extended until at least 2040.

4.1. Legal basis

This antitrust case began in 2003 when the European Commission received a private complaint alleging that the exclusive license to explore and exploit lignite granted to PPC with a 1959 legislative decree and the 1973 mining code, was contrary to the EU market rules.

Responding to this complaint in 2008, the EC found that the exclusive rights on lignite enabled PPC to maintain or strengthen its dominant position in the wholesale electricity supply market by blocking any new entry into the market to the detriment of Greek consumers (European Commission, 2008). Consequently, the EC laid down specific measures to remedy the anti-competitive effects of the infringement and pushed for the opening of the Greek lignite market to competition (European Commission, 2009).

PPC, supported by the Greek government, filed two appeals with the General Court of the European Union (GCEU) and requested the annulment of the EC’s two decisions. However, the GCEU with its final decision (GCEU, 2016), 13 years after the initial complaint, rejected all arguments raised by PPC, thus obligating Greece to render lignite deposits accessible to other companies besides PPC. In the meantime, the economic prospects of lignite plants had drastically deteriorated and the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement was already leading the EU to major policy revisions.

In parallel, Greece was faced with an unprecedented financial crisis and had been subject to an economic adjustment program, supervised by the country’s main lenders, represented by the EC, the European Central Bank, the European Stability Mechanism, and the International Monetary Fund, henceforth “the Institutions”.

4.2. The first privatization attempt – “small PPC”

The first attempt by the Institutions to impose the unbundling of PPC’s lignite assets came in 2012 before the final General Court’s decision. The second economic adjustment program for Greece specifies that “the Greek government has now committed to grant access to 40 percent of lignite capacity to the incumbent’s competitors by end-March 2012 and it has put forward the idea of selling hydro plants, which could be combined with the sale of lignite plants” (European Commission, 2012).

This plan started to materialize two years later when the law of “small PPC” was approved by the Greek Parliament (Greek Government, 2014). The law established a new vertically integrated power company to which 30% of PPC’s total electricity producing capacity and 30% of PPC’s clients would be sold.

Reactions to the law by all opposing parties in the Greek Parliament echoed their positions against the privatization of the PPC and other Greek assets, as well as most measures imposed to Greece by the Institutions. Environmental NGOs opposed this law as well, albeit for a completely different reason. The sale of lignite assets to private companies would prolong the lignite-based electricity model in Greece, at the detriment of climate, nature, public health and the economy.

The law for “small PPC” was finally adopted but was never implemented because of the shift in power after the national elections in January 2015. The new government formed by left party SYRIZA was against privatizing any part of PPC, including its lignite assets.

4.3. The second privatization attempt

Τhe second and more threatening attempt to enforce the implementation of the EU Court’s antitrust decision regarding PPC’s lignite monopoly came almost three years later. In 2017, the Institutions formulated a Supplemental Memorandum of Understanding (European Commission et al, 2017) which included nine structural measures in the energy sector. Their intention was “to bring Greek energy markets in line with EU legislation and policies, make them more modern and competitive, reduce monopolistic rents and inefficiencies, promote innovation, favour a wider adoption of renewable energy and gas, and ensure the transfer of benefits of all these changes to consumers”. The cornerstone of these measures was the divestment of 40% of PPC’s lignite-fired generation capacity and related assets to existing or new alternative suppliers and other investors.

After Greece agreed to the sMoU intense negotiations on the contents of the lignite sale “package” between the Greek government and the European Commission followed. The EC’s willpower prevailed (European Commission, 2018). Thus, in April 2018 the Greek Parliament voted Law 4533/2018 (Greek Government, 2018), describing the assets to be sold, the procedures that would be followed and associated measures. Setting aside differences and objections on specific articles of Law 4533/2018, the three biggest political parties in Greece supported the lignite sale in principle, because they understood that the sale would ensure the continuation of the lignite-based electricity model. The Greek communist party was the only one opposing the lignite sale. However, its position stemmed from its general opposition against all privatizations of public assets.

Environmental NGOs and think tanks in Greece, as well as ClientEarth, a London-based organization of environmental lawyers, on the other hand, strongly opposed the overall concept of selling a portion of PPC’s lignite assets to other power companies (Mantzaris, 2018; Holmes & Diamantopoulou, 2019). They addressed the very core of the Institutions’ rationale which assumed that breaking the PPC’s monopolistic access to the country’s lignite deposits, would increase the competitiveness in the electricity market, and, consequently, lead to lower electricity prices for the benefit of the consumers and the Greek economy. They argued that the imposed sale would have the completely opposite effect as it would extend lignite’s role in Greece’s electricity mix, which would, in turn, have catastrophic effects for the consumers, PPC, and the Greek economy for a variety of reasons.

First, the revision of the EU ETS Directive aimed at stimulating the carbon price signals and salvage the EU’s flagship climate mitigation policy instrument. Since the Greek lignite plants burn the worst quality lignite in the EU, they emit the most CO2 per unit of electricity produced. Thus, they would be more vulnerable economically to major carbon price increases, directly burdening the operating costs of lignite plants. Second, the EU’s new BATc rules on pollution from power plants that were agreed upon at the EU level in April 2017 required expensive retrofits for the highly polluting lignite plants, thus further deteriorating the economics of lignite plants. Third, conventional fossil fuel electricity generation technologies were already facing significant competition from renewables, that were becoming progressively cheaper.

The aforementioned arguments were presented in two letters sent by the networks of environmental organizations “Europe Beyond Coal” and “Climate Action Network Europe”, the organization of environmental lawyers, ClientEarth, the British climate think tank, Sandbag and the Greek environmental think tank, “The Green Tank”, to the Commissioners for Climate Change and Energy (EBC et al., 2019a) and Competition (EBC et al., 2019b). Interestingly, Commissioner Cañete replied that the objective of the lignite divestiture “by no means entail the construction of new coal power plants (Meliti 2) or the extension of the licenses of the existing ones” (Cañete, 2019), while Commissioner Vestager emphasized “that none of the investors has shown interest in the construction of such a unit” (Vestager, 2019). Following these answers, the NGOs requested from both Commissioners to modify the Sales Purchase Agreement (SPA) by removing the production license for Meliti 2 and ensuring that the two lignite plants in Megalopoli as well as Meliti 1 included in the package would be retired by 2027 and 2028, respectively, when their environmental permits expired. It was the first time that 2028 was mentioned as a possible end of the lignite activity related to the three plants that were up for sale (EBC et al., 2019c). Eventually 2028 was adopted by the Greek Prime Minister as the phase out year for lignite (Mitsotakis, 2019).

4.4. The Greek capacity mechanism

The deteriorating economics of Greek lignite plants was a major obstacle impeding the lignite sale. To remedy this, PPC and the Greek government engaged into intense efforts to subsidize the Greek lignite plants via a capacity mechanism.

After the outcome of the trilogue negotiations on the recast EMR in December 2018 and the failure to ensure long-term financial support for Greece’s lignite plants, the government’s strategy shifted towards exploiting the abovementioned “grandfathering” loophole in the EMR to exempt Greek lignite plants and make them eligible for longer-term subsidies (Energypress, 2018) before the entry into force of the new Regulation.

The government proposed a capacity mechanism which would enable Greek lignite plants to obtain capacity contracts until 2033 and requested the EC’s (DG COMP) urgent approval prior to the July 2019 deadline. The process was initially very opaque as only the Greek government and DG COMP were aware of the proposals’ contents. However, actions by environmental NGOs and Spanish MEP Marcellesi (European Parliament, 2019) exerted pressure which forced the government to open the proposal for public consultation on April 2019, just for 18 days.

The Green Tank and ClientEarth participated in the consultation, arguing that the proposed capacity mechanism had two major problems (The Green Tank, 2019a; ClientEarth, 2019). First, it did not prove its necessity since: a) necessary market reforms included in the target model were not implemented at that time; b) a Resource Adequacy Assessment (RAA) did not accompany the proposal, while the most recent RAA by the Greek Independent Power Transmission Operator (ADMIE) failed to adequately prove a security of supply problem for Greece that could not be remedied without a permanent market-wide capacity mechanism, such as the one proposed; c) alternative forms of a capacity mechanism, such as a strategic reserve, had not been considered and comparatively evaluated with the proposed one. Second, the proposed capacity mechanism attempted to unduly support lignite plants at the expense of other technologies and violated the recently agreed recast EMR, as well as the Guidelines on State aid for environmental protection and energy.

As the deadline of July 4, 2019, for exploiting the loophole of the recast EMR was approaching and the crucial approval of the Greek capacity mechanism by DG COMP was still missing, the Greek government made a desperation move: on the very last day the Greek Parliament operated before closing for the national elections, the Minister of Environment and Energy tabled an amendment to an irrelevant bill unilaterally approving the market-wide capacity mechanism it was still negotiating with the EC. The amendment was adopted by the Greek Parliament on June 7, 2019, thus before the July 4 deadline. However, without the Commission’s approval this mechanism would constitute illegal State aid. This point was indirectly verified by the PPC’s CEO, who, on June 19, 2019, sent a letter to the Commissioner for Competition Vestager pleading with her to approve the Greek capacity mechanism to partially salvage PPC’s investment in Ptolemaida 5 (PPC, 2019a).

Despite these desperate efforts by the Greek government and the PPC, the European Commission did not approve the Greek capacity mechanism before the recast EMR came into force on July 4, 2019. Therefore, none of the existing Greek lignite plants would be eligible to participate in any capacity mechanism beyond July 2025, whereas the new lignite plant “Ptolemaida 5” would be unable to participate at all, thus further deteriorating its economic prospects.

4.5. The lignite sale attempts

While the Greek government and PPC were trying to extract an approval from the EC for the participation of lignite plants in a capacity mechanism, PPC moved forward with the actual sale of the lignite assets as agreed with the Institutions and enshrined into law.

In July 2018, PPC completed the evaluation of the companies that expressed interest in acquiring 100% of the share capital of the two disinvested companies that were created from PPC according to Law 4533/2018. Six companies were selected to submit binding offers (PPC, 2018). Following successive postponements of the deadline to make the lignite assets more attractive, the deadline approved by DG COMP was February 8, 2019. After a few days, PPC announced the failure of the highly anticipated sale (PPC, 2019b).

The single valid bid submitted by the Greek company Mytilineos S.A. concerned only one of the three lignite plants up for sale, while the reported €25 million offer was rejected because it was six times smaller than the corresponding appraisal of the independent evaluator. A second bid for all three lignite plants was also submitted by Czech company Sev.en Energy in collaboration with GEK TERNA. However, it was rejected upon reception since it contained a mechanism of sharing losses and profits between the new owners and PPC which did not comply with the terms of the SPA and because the offer of €103 million was almost three times lower than the evaluator’s appraisal (Liaggou, 2019).

Amid concerns that after the first failure the Institutions would force PPC to part with its valuable hydroelectric plants, the PPC’s CEO reiterated the commitment of the company to repeat the same tender and expressed his optimism that the second effort would be successful, provided DG COMP approved the capacity mechanism. The tender procedure was relaunched on March 8, 2019 (PPC, 2019c) and a week later interest was expressed by six companies, five of which, had expressed interest in the first tender (PPC, 2019d). Even though there was no floor price set by an independent evaluator in this second attempt, no company submitted a binding offer on the PPC lignite package or parts of it (PPC, 2019e).

4.6. After the failure to sell

The result of the general elections on July, 2019 meant another shift in government. The two failed attempts to sell PPC’s lignite assets proved beyond any reasonable doubt that the energy market saw no future in exploiting Greek lignite, especially under conditions of escalating carbon prices. This realization together with PPC’s rapidly deteriorating economics, in large part due to its loss-making lignite industry (The Green Tank, 2019b) led the new government to the decision to phase out lignite by 2028. The historic announcement was made by the newly elected Prime Minister in the UN Climate Action Summit in New York on September 23, 2019 (Mitsotakis, 2019; EBC, 2019d).

In December 2019, the phase out decision was enshrined in PPC’s new business plan (Koutantou, 2019) as well as in the NECP that Greece submitted to the EC (Ministry of Environment and Energy, 2019), in line with the EU’s added climate ambition as presented in the EU Green Deal. Both documents included a detailed phase out timeline, according to which all existing lignite plants would retire by 2023 and only the new “Ptolemaida 5” lignite plant, which was still under construction at the time, would operate between 2023 and 2028.

These historic developments constituted the healthiest turn in Greece’s recent energy and climate policy and essentially nullified the whole idea of breaking PPC’s lignite monopoly by allowing access to lignite assets to other power companies, imposed through the sMoU. However, the EC refused to admit this was the case and insisted on PPC’s compliance with the GCEU’s judgment.

To address DG COMP’s uncompromising attitude, the Greek government proposed several solutions. After several rounds of negotiations, a deal was struck in 2021 (European Commission, 2021) and was enshrined into national legislation (Greek Government, 2021). It involved bilateral Power Purchase Agreements formed between PPC and other power suppliers, through which PPC would offer rival suppliers electricity packages equal to percentages of its lignite-based electricity production the previous year at prices below day-ahead market (DAM) prices over a three-year period. Specifically, in 2021, PPC would sell electricity packages equalling 50% of the lignite-based electricity it produced in 2020, while in 2022 and 2023, the utility would offer for sale electricity equal to 40% of the lignite-based production in the respective previous years.

The first auctions took place on September 2021 and sold 978 GWh in total, surpassing the 893 GWh corresponding to PPC’s 2021 obligation (Energypress, 2021a). Moreover, 1740 GWh were sold in October 2021 (Energypress, 2021b), but that quantity was smaller than PPC’s 2022 obligation of 2136 GWh. The implementation of the antitrust agreement further deteriorated in 2022, as the electricity package PPC offered to sell in October 2022 to fulfil its obligation for the first three quarters of 2023 did not attract any interest from suppliers and traders due to the high risk involved and the financial pressure stemming from the energy crisis. With one last lignite package remaining to be offered by PPC, Greece submitted a request to the EC to have the antitrust agreement abolished (Energypress, 2022). Apparently the request was not accepted.

Finally, the case, which begun almost 15 years before, was settled with the sale of the last package of “lignite energy” by PPC on November 1st 2023 (PPC, 2023).

5. Conclusion and policy implications

The four Institutions involved in Greece’s economic rescue programs and the European Commission in particular, insisted on the partial privatization of PPC’s lignite assets based on a case that was initiated 20 years ago when the economic realities of lignite and EU climate and energy policy were vastly different. A variety of options were attempted to remedy the distortions of the Greek electricity market. However, all neglected a fundamental truth: Competition for the benefit of electricity consumers and the Greek economy cannot be stimulated through lignite, a fuel which has been rendered uneconomic and obsolete by the EU-led global effort to fight against the rapidly escalating climate crisis. Furthermore, it is evident that even within the European Commission there is a real problem of coordination between different Directorate Generals (DG COMP in particular) as climate policy has not been incorporated horizontally into other policies.

The double failure to attract the interest of the energy market in Greece and abroad for PPC’s lignite assets proved beyond any reasonable doubt the flawed rationale of the EC’s DG COMP when it was imposing the lignite sale on PPC and the Greek government, through the supplemental Memorandum of Understanding, in 2017.

However, blind, one-dimensional approaches based on general theories on the benefits of a fully liberalized market, such as those imposed by the four Institutions to Greece, could have hindered the country’s sustainability prospects. Had the economics of Greek lignite plants not been as dismal as they are, fresh funds could have been injected in Greece’s lignite industry. This could have, in turn, led to additional market distortions, which would have prolonged Greece’s dependence on lignite at the detriment of the climate, nature, public health and the Greek economy.

The implications are of an even bigger scale. If the tactics and measures imposed by the Institutions were applied in countries that are not EU member states, in parts of the world lacking the EU’s robust energy and climate institutional framework, the shift away from lignite would have been even harder. Hence, the example of the Greek lignite divestment should be carefully analyzed by the Institutions and the conclusions drawn should lead to significant changes in the way that economic rescue programs are designed and implemented in the future.

The role of the environmental NGOs and think tanks in these policy developments was critical. They provided fact-based analysis and well-documented arguments against the prolongation of the lignite-based electricity model in Greece, bringing also to light several of the attempts for derogations that would push Greece in the opposite direction.

Nevertheless, the efforts by environmental NGOs and think tanks from Greece and the EU alone would not have been enough to prevent a negative outcome for the sustainability of the country’s entire energy future, had Greece not been a member state of the EU. It was the revision of EU-ETS Directive that was responsible for the escalation of the carbon prices; it was the new Best Available Techniques conclusions in conjunction with the Industrial Emissions Directive which caused the need for expensive retrofits for Greece’s lignite plants; it was the Electricity Market Regulation that ceased massive subsidies towards lignite plants. Finally, it is now the European Green Deal and the EU Climate Law, which render a return to lignite completely unrealistic.

The Greek lignite divestment case underlines, therefore, the contradiction and inconsistency between different departments of EU policy making. While the EC was pressuring Greece to sell PPC’s lignite assets and prolong the polluting lignite-based electricity model, it was also developing the “Clean Energy for all European package” which aimed at shifting EU’s energy model towards renewables.

For national decision makers, the recent history of lignite in Greece should prove that the hunt for derogations and loopholes in EU legislation to prolong the end of fossil fuels is not only fruitless but also not politically smart. It is costly in terms of funds, political capital, and time to implement real solutions to shield the country against energy crises such as the recent one. Had PPC and the Greek government not been so focused on extending the lifetime of lignite, PPC could have avoided spending more than €1.4 billion to construct the biggest “cross-party error” in Greece’s energy policy as former Minister of Environment and Energy K. Hatzidakis characterized the construction of PPC’s new lignite plant “Ptolemaida 5”.

Furthermore, if instead of trying to implement a fundamentally wrong solution, the government and Greek political parties worked on designing a socially just transition of Greece’s two lignite regions much earlier, more time would have been available for their undoubtedly challenging economic transformation.

Finally, Greece could have been able to scale up the deployment of renewables much earlier and the country would have had much lower electricity prices, smaller dependence on fossil gas and, therefore, would have been much better prepared to deal with the energy crisis.

The political choices made by Greek decision makers regarding Greece’s lignite industry were short-sighted and failed to recognize the wave of change that was coming regarding lignite to the detriment of the Greek citizens. The same mistake should not be repeated. At a time when Greece is redesigning its energy future through the revision of its National Climate and Energy Plan, any attempts to stall the shift towards a fully renewables-based electricity model will be detrimental for the climate, the national economy, and the public interest.

References

- Cañete, M.A. (2019). Reply of Commissioner for Climate Change and Energy Miguel Arias Cañete to the letter of NGOs of 24th January 2019. https://bit.ly/38QvXW4

- ClientEarth. (2019). Observations on the proposed Greek capacity mechanism. https://bit.ly/3SJGfNn

- Climate Action Network (CAN). (2017, March). CAN Europe position on capacity mechanisms. https://shorturl.at/efiqS

- Council of the European Union (2017, December 20). Outcome of proceedings on Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council on the internal market for electricity (recast). https://bit.ly/3qyp2XR

- Energypress, (2018, June 27). CAT eligibility vital for prospects of PPC units sale, chief notes. Energypress https://bit.ly/38QqLBx

- Energypress, (2021a, September 28). PPC fulfils 4Q antitrust lignite obligation for supply to rivals. Energypress. https://bit.ly/3wEdass

- Energypress, (2021b, October 13). PPC lignite-fired electricity package sales to rivals for ’22 progressing fast. Energypress. https://bit.ly/3Do9vTi

- Energypress, (2022, December 14). Suppliers, traders reject PPC lignite power packages for ’23. Energypress. https://bit.ly/3kT9OPx

- Environment Council. (2017, March 1). Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2003/87/EC to enhance cost-effective emission reductions and low-carbon investments – General Approach. https://goo.gl/gFKJMf

- European Commission (2008). European Commission, Decision C (2008) 824. Summary of Commission Decision of 5 March 2008 relating to a proceeding under Article 86(3) of the EC Treaty on the maintaining in force by the Hellenic Republic of rights in favour of Public Power Corporation SA for the extraction of lignite (Case COMP/B-1/38.700) (notified under document number C(2008) 824). https://bit.ly/38Z1rtt

- European Commission. (2009). European Commission Decision C (2009) 6244. Summary of Commission Decision of 4 August 2009 relating to a proceeding under Article 86(3) of the EC Treaty establishing the specific measures to correct the anti-competitive effects of the infringement identified in the Commission Decision of 5 March 2008 on the granting or maintaining in force by the Hellenic Republic of rights in favour of Public Power Corporation S.A. for the extraction of lignite (Case COMP/B-1/38.700) (notified under document C(2009) 6244). https://bit.ly/2M3Hitd

- European Commission. (2012). The Second Economic Adjustment Program for Greece. European Economy. Occasional Papers 94, March 2012. https://bit.ly/3nYj94n

- European Commission. (2016). Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council on the internal market for electricity (recast). https://bit.ly/2LUYmkW

- European Commission. (2017). Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2017/1442 of 31 July 2017 establishing best available techniques (BAT) conclusions, under Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, for large combustion plants, Off. J. Eur. Union 17(8), 2017. https://bit.ly/3qBvygj

- European Commission. (2018). COMMISSION DECISION of 17.4.2018 establishing the specific measures to correct the anti-competitive effects of the infringement identified in the Commission Decision of 5 March 2008 on the granting or maintaining in force by the Hellenic Republic of rights in favour of Public Power Corporation S.A. for extraction of lignite Case AT.38700 – Greek lignite and electricity markets. https://bit.ly/3HBzh7Z

- European Commission. (2021). Final Commitment Text 01/09/2021. Case COMP 38.700 – Greek Lignite and electricity markets. Commitments to the European Commission. https://bit.ly/3H9G7B2

- European Commission, The Hellenic Republic & Bank of Greece. (2017). Supplemental Memorandum of Understanding (second addendum to the Memorandum of Understanding) between the European Commission acting on behalf of the European Stability Mechanism and the Hellenic Republic and the Bank of Greece. https://bit.ly/3qvho0n

- European Council. (2017, April 28). Voting calculator results for the Large Combustion Plants Best Reference document (LCP BREF) https://bit.ly/3Y9ohoV

- European Environmental Agency (EEA). (2023). Greenhouse gases – data viewer https://bit.ly/2HzzrRh

- European Environmental Bureau (EEB), the Health and Environment Alliance (HEAL), Climate Action Network (CAN) Europe, WWF & Sandbag (2016). Lifting Europe’s Dark Cloud: How cutting coal saves lives. https://bit.ly/3L2ZG0Y

- European Parliament (2017, February 2). Cost-effective emission reductions and low-carbon investments Amendments 147 and 162. https://bit.ly/46WCDy4

- European Parliament. (2019). Question for written answer P-000971-19 to the Commission according to Rule 130 by Florent Marcellesi (Verts/ALE) with subject “Greek capacity mechanism”. https://bit.ly/2LA1X8m

- European Parliament and the Council. (2018). Directive (EU) 2018/410 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2018 amending Directive 2003/87/EC to enhance cost-effective emission reductions and low-carbon investments, and Decision (EU) 2015/1814, Off. J. Eur. Union 19(3), 2018. https://bit.ly/3DoZfKi

- European Parliament and the Council. (2010). Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 November 2010 on industrial emissions (integrated pollution prevention and control), Off. J. Eur. Union 17(12), 2010. https://bit.ly/3rvKpi5

- European Parliament and the Council. (2019). Regulation (EU) 2019/943 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on the internal market for electricity, Off. J. Eur. Union 14(06), 2019. https://bit.ly/40KL9f3

- European Parliament and the Council. (2015). Decision (EU) 2015/1814 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 October 2015 concerning the establishment and operation of a market stability reserve for the Union greenhouse gas emission trading scheme and amending Directive 2003/87/EC. Off. J. Eur. Union 09(10), 2015. https://bit.ly/3JnKiMA

- Europe Beyond Coal (EBC), Climate Action Network (CAN), Sandbag, Client Earth, & The Green Tank (2019a). Letter of the environmental organizations to EU Commissioners Cañete and Šefčovič. https://bit.ly/39HohEM

- Europe Beyond Coal (EBC), Climate Action Network (CAN), Sandbag, Client Earth, The Green Tank. (2019b). Letter of the environmental organizations to EU Commissioner Vestager. https://bit.ly/2Kzf9ty

- Europe Beyond Coal (EBC), Climate Action Network (CAN), Sandbag, ClientEarth, & The Green Tank. (2019c). Reply of the environmental organizations to EU Commissioners Cañete and Vestager. https://bit.ly/2KAre1E

- Europe Beyond Coal (EBC). (2019d). Greece and Hungary to phase out coal-fired electricity. Press Release. https://bit.ly/3bVvd4e

- EU ETS Union Registry (2022, May 4). Compliance Data for 2021. https://bit.ly/3Onys3M

- Famellos, S. (2017, February 28). Speech by S. Famellos, Alternate Minister of Environment and Energy, Greece in the Environment Council on the reform of the EU ETS. https://bit.ly/3rAak8q

- Flisowska, (2018, November 12). Electricity market must serve higher climate ambition. Euractiv. https://shorturl.at/beHRS

- General Court of the European Union (GCEU). (2016). Judgment of the General Court of 15.12.2016, (Case T‑169/08 RENV). Competition — Abuse of dominant position — Greek markets for the supply of lignite and of wholesale electricity — Decision finding an infringement of Article 86(1) EC in conjunction with Article 82 EC — Granting or maintaining in favour of a public undertaking of rights to exploit public deposits of lignite — Definition of the relevant markets — Existence of inequality of opportunity — Obligation to state reasons — Legitimate expectations — Misuse of powers — Proportionality. https://bit.ly/2NkUgDr

- Greek Government. (2014). Establishment of a new, vertically integrated power company. Law 4273/2014, Government gazette A’ 146. https://bit.ly/3L8IwyG

- Greek Government (2018). Structural measures for access to lignite and the further opening of the wholesale electricity market and other provisions. Law 4533/2018, Government Gazette Α’ 75/27.04.2018. https://bit.ly/3qXWL2F

- Greek Government (2021). Transposition of Directive (EU) 2018/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of December 11, 2018 “on the amendment of Directive 2012/27/EU on energy efficiency”, adaptation to Regulation 2018/1999/EU of the European Parliament and of Council of 11 December 2018 on the governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action and Commission Delegated Regulation 2019/826/EU of 4 March 2019, “amending Annexes VIII and IX of Directive 2012/ 27/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on the content of comprehensive assessments of the potential of efficient heating and cooling” and related regulations for energy efficiency in the building sector, as well as the strengthening of Renewable Energy Sources and competition in the electricity market, and other urgent provisions. Law 4843/2021 Government gazette Α’193.2021. https://bit.ly/3XLbaKR

- Holmes, S. & Diamantopoulou E., (2019, January 31). End of the Road for the Sale of Greece’s dirty fuel of the past. Energy Post. https://bit.ly/3ECvVR4

- Koutantou, A (2019, December 16). Greece’s PPC wants to speed up coal phase-out, boost renewables by 2024. Reuters. https://reut.rs/3oYbzrK

- Liaggou, C. (2019, February 9). Tender for PPC units ends in utter failure. Kathimerini. https://bit.ly/3o0aMFv

- Mang, S. (2018). EXPOSED: €58 billion in hidden subsidies for coal, gas and nuclear New EU rules would allow big energy companies to continue cashing in on dirty energy. Greenpeace. https://bit.ly/35OWi56

- Mantzaris, N. (2017, February 14). ETS vote will determine Greece’s energy future. Euractiv. https://shorturl.at/jvzW5

- Mantzaris, N. (2018, January 25). Greek coal: The EU’s dirty little secret. Euractiv. https://bit.ly/365CZor

- Ministry of Environment and Energy (2018). Greece’s draft National Energy and Climate Plan. https://bit.ly/2WpuSel

- Ministry of Environment and Energy. (2019). Greek National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP). https://bit.ly/3EnR0hP

- Mitsotakis, K. (2019). Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis’ speech at the UN Climate Action Summit. https://bit.ly/3qB4Jc9

- Neslen, A. (2016, November 2). Greece set to win €1.75bn from EU climate scheme to build two coal plants. The Guardian. https://bit.ly/3DqqtAl

- Panagiotakis, E. (2016, November 30). PPC CEO: lignite units not profitable. Economist conference, Athens Greece. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SjsFEt6wT7k

- PPC. (2018). Evaluation of the participants in the first phase of the competitive process for the acquisition of 100% of the capital share of the disinvested companies Lignitiki Melitis S.A. and Lignitiki Megalopolis S.A. Press Release. https://bit.ly/3nVCrre

- PPC. (2019a). Letter from Em. Panagiotakis to the Commissioner of Competition of the European Commission Margrethe Vestager regarding the issue of the capacity mechanism. Press Release. https://bit.ly/35RvTUl

- PPC. (2019b). Declaration on the outcome of the first tender process. Press Release. https://bit.ly/3LtrWdw

- PPC. (2019c). Re-launch of the tender procedure for the divestment of lignite –fired generation units of PPC S.A. Press Release. https://bit.ly/3Nfh3h0

- PPC. (2019d). Submission of Expression of Interest by Ιnterested Parties for the acquisition of 100% of the share capital of the Meliti and /or the Megalopoli Divestment Businesses. Press Release. https://bit.ly/3ncJOQx

- PPC. (2019e). Update on the lignite divestment tender. Press Release. https://bit.ly/3LbuA6k

- PPC (2023). PPC: A 15-year pending case was finally closed. Press Release. https://bit.ly/4ffk24t

- The Green Tank. (2019a). Comments on the public consultation on the proposed Greek capacity mechanism. https://bit.ly/3nUH70g

- The Green Tank. (2019b). The economics of Greek lignite plants. End of an era. https://shorturl.at/mopzU

- The Green Tank. (2023). Trends in electricity production – December 2022. https://bit.ly/3Y0XlZK

- United Nations (2015). Paris Agreement. https://bit.ly/2L3Ao1a

- Verroiopoulos, M. (2017, December 18). Speech by M. Verroiopoulos, Greek General Secretary of Energy in the Transport, Telecommunications and Energy Council, on the Internal Electricity Market. https://shorturl.at/cdgkr

- Vassos, S., & Vlachou, A. (1996). EVALUATING THE IMPACT OF CARBON TAXES ON THE ELECTRICITY SUPPLY INDUSTRY. The Journal of Energy and Development, 21(2), 189–215. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24808803

- Vestager, M. (2019) Reply of Commissioner for Competition Margrethe Vestager to the letter of NGOs of 24th of January 2019. https://bit.ly/3quZJFX