by James Bushnell

Taxing carbon at the border is a lot more complicated than you may think, explains James Bushnell at the Energy Institute at Haas. The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) imposes a tax on imported goods that is designed to reflect the carbon content of those goods. But CBAM has flaws that must be addressed.

It taxes the carbon in imported inputs supplied to EU producers, but not the carbon of those same inputs if they are imported as finished products. Taking (and trusting) detailed emissions measurement will be difficult. There is a risk of “reshuffling”: suppliers send their clean goods to the EU, but still make dirty goods that they just send elsewhere, limiting the expected cuts in global emissions. There’s no carbon price relief for EU producers who are selling their products outside of Europe. And the CBAM could incentivise other regions to implement carbon pricing schemes that game the system, thereby rewarding inputs that are more carbon-intensive than EU rivals (something similar happened in the U.S. when it tried the Clean Power Plan). These flaws should be taken into account in the run up to the full implementation of CBAM in 2026, says Bushnell.

Confronting the leakage of emissions to other jurisdictions

One of the biggest challenges facing any jurisdiction that is trying to mitigate climate change through carbon pricing, caps, or really any regulation that raises costs on local businesses, is confronting the leakage of emissions to other jurisdictions. Some businesses will seek out places with less regulations and lower costs, others just won’t be able to compete with businesses already producing in unregulated areas and countries.

For more than a decade, the most common tool for trying to stem leakage from regions with cap-and-trade systems has been the free allocation of emissions allowances – the currency of cap-and-trade systems – to businesses that continue operations in the local market. This technique, called output-based allocation (OBA), is distinct from other forms of free allowance giveaways in that the allowances are linked to the recipient’s production in the capped region.[1] The idea is that firms get rewarded (in the form of allowances) for not moving their business, but still have an incentive (driven by the price in the carbon market) to reduce their emissions rate. In other words, they get an incentive to still produce, but in a less carbon intensive way.

It’s an elegant partial solution to the leakage problem in theory, but in practice it has been subject to measurement challenges and political wrangling, with the result being that allocations have been tied as much to political influence as to real leakage risk. The free allocation of allowances also means foregone revenues for the jurisdictions that might otherwise auction those allowances off.

From Allocation to Import Tariffs

Output based allocation now seems to be a quaint, neo-liberal idea in this era of high-tariffs and trade wars. The new tool de jure is the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). While this is a general sounding name, in practice CBAM has come to mean a tax on imported goods that is designed to reflect the carbon content of those goods. To politicians who want to prioritise protecting local industries and raising funds, CBAM (just like any other import tariff) is very appealing. Of course, the point is not supposed to be protectionism, but rather trying to restore a competitive playing field in which local industries can still compete while also paying for their carbon emissions.

Europe has been leading the way on the CBAM idea. The EU is in a trial phase of its CBAM right now, and plans to implement its first phase of binding regulations in 2026.

In the past I have found the idea of a CBAM a very appealing, maybe even necessary, tool for trying to achieve some level of coordinated, worldwide carbon reductions. However, there are several aspects of the EU’s CBAM implementation that have struck me, and others, as potential land mines that could dilute or even negate the benefits of the policy.

CBAM’s flaws

First, the EU’s CBAM is initially going to apply to only seven categories of products – aluminium, iron, steel, fertilisers, cement, electricity, and hydrogen. This means that a carbon price will be applied to the imported steel that goes into a car produced in Europe, but a carbon price will not be applied to the steel if the entire car is built somewhere else and shipped to Europe. While the targeted products are amongst the most carbon intensive, many are also key inputs into finished products that are traded internationally. Work by a group of European economists has concluded that this limited-goods CBAM “only marginally improves on the scenario without [any] border adjustments.”

Second, the CBAM will allow individual sources to claim source-specific carbon intensities. Measuring and verifying the carbon intensity of a specific facility’s production methods can be a time-consuming process – just ask the Low Carbon Fuel Standard team at the California Air Resources Board. While “clean” firms will have an incentive to get verified as clean, it is not clear how quickly this process will work, or how much EU oversight will be applied to verification. I suspect the difficulty of coming up with these carbon scores is one of the big reasons the EU is starting out with only seven product categories. They say that starting in 2026 they will study expanding the CBAM to more goods, possibly by 2030.

Beyond the time and effort required for measurement and verification, source specific carbon scores create another major downside risk: reshuffling. While the definition of reshuffling, like leakage, is somewhat fluid, the general idea is that suppliers divert the clean goods to the regulated regions, but still make dirty goods that they just send elsewhere. Europe may attract a lot of low carbon fertiliser and aluminium, but as long as there is enough demand for high carbon fertiliser and aluminium elsewhere, it won’t really change global emissions, commodity prices, or help local industries as much as expected.

Third, the CBAM will raise costs of some imported goods, but the EU decided against any kind of tax refund for exported goods. This may be as much a policy choice as an inherent weakness of a CBAM,[2] but it means that European producers will still face a tilted playing field when they try to sell their goods outside of Europe.

Fourth, and this is where things get really complicated, the CBAM will reduce its border carbon taxes on imported goods to account for the carbon prices in their countries of origin. At first glance, this sounds both fair and positive. Other countries that apply carbon prices on their industries will be both doing a good thing for the globe, and be rewarded for (or at least not punished for it) it in the European market. Indeed, this inducement for other countries to join the pricing “carbon club,” has been pointed to as a major external benefit of the CBAM policy.

Are you good enough to join the “carbon club”?

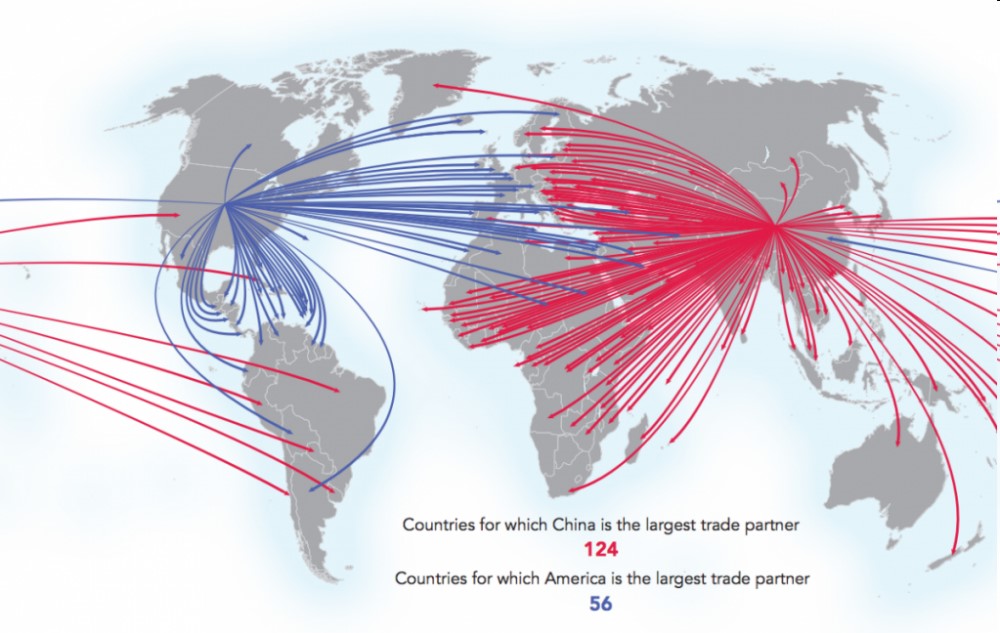

But what kind of club are they going to want to join? The problem is that, as I understand it, there is not a good plan for distinguishing among countries with carbon caps, carbon taxes, and carbon performance standards (or intensity standards).[3] This third group includes China. You may have heard that China is kind of an important global exporter.

The much-hyped Chinese carbon market operates as a tradeable performance standard (TPS), one that regulates the carbon emissions rate of sources. For example, in electricity the regulation targets a fleet average tons/MWh rather than placing a firm cap on the tons. All firms have to surrender permits associated with their emissions, but they will also be allocated permits per unit of output (e.g., per MWh) based upon a benchmark. Firms that are cleaner than the benchmark will receive more allowances in free allocation than they have to surrender to pay for their measured emissions.

The impact of tradable performance standards (TPS) on the incentives of regulated firms is very different than under a pure cap or tax. Basically, a TPS lowers the cost of those producers who are cleaner than “average” – or technically cleaner than the standard – and raises the cost of those dirtier than the standard. The higher the carbon price, the more it subsidises those plants that are cleaner than the standard. This is not necessarily the worst thing in and of itself, although most economists prefer a more traditional carbon cap to intensity standards. Goulder et al, found that abatement costs under the Chinese TPS would be about 35% higher than under a comparable cap and trade program.

Different systems will cause problems

Problems really emerge when the two systems are mixed together in competitive trade. I’ve thought about this a lot and even wrote a paper with Stephen Holland, Jon Hughes and Chris Knittel on this. The context was the 2014 iteration of the Clean Power Plan (CPP). The CPP could have resulted in some states with performance (“rate”) standards effectively subsidising the production of power from their natural gas plants (while penalising production from coal). If those states traded electricity with a state with a more conventional cap, plants in the capped state would be at a double disadvantage. Their gas plants would pay a carbon price, while their competitors’ would be subsidised. One of the other insights of the paper was that the CPP, by allowing states the choice of caps or intensity standards, could push states into the latter simply because of the competitive advantages it might create for them.

It is easy to imagine a scenario like this evolving from a CBAM that doesn’t properly distinguish between countries with conventional caps and those with intensity standards. Consider two Chinese fertiliser plants, one uses natural gas as a feedstock and the other uses coal. If China sets its standard somewhere between the emissions rates of these two technologies, the “clean” fertiliser in China is going to be implicitly subsidised by China’s carbon pricing system – basically the dirty fertiliser plant is sending money to the cleaner one.

If the dirty fertiliser was heading to Europe anyway, imposing a carbon cost on the dirty fertiliser plant locally doesn’t really cost it anything: it was going to have to pay those costs to the EU anyway and now its local carbon cost will be offset by the CBAM credits. But the local carbon costs paid by the dirty firm is going to fund more fertiliser production from the cleaner Chinese firm. In this way the subsidy to the clean fertiliser firm, which may in fact still be dirtier than the average European firm, is at least partially being supported by the CBAM.[4]

Is there a better way?

So to sum up the potential landmines in the field of CBAM, we have:

- Taxing the carbon in imported inputs to local producers, but not the carbon of those same inputs if they are imported as finished products.

- Granular emissions measurement that creates vulnerabilities to reshuffling.

- No carbon price relief for local producers who are selling their products outside of Europe.

- Attempts to account for carbon pricing in other countries could backfire and at least partially reward sources that are actually being subsidised by their local government’s carbon pricing scheme.

- This subsidy dynamic could push countries toward adopting less efficient TPS style carbon pricing, rather than more conventional carbon caps or taxes.

Now as anyone who has made it this far will realise, this stuff is really complicated and it’s really hard to navigate all these problems. Some have proposed changes to the details of implementation of the CBAM mechanism, others an alternative formula for the border tax. As I stare at this list, however, I come to the conclusion that there is at least one instrument that avoids all of these problems. Strangely enough, that instrument is output based allocation, the very tool being phased out by the EU in favour of CBAM.

There is one big downside to O-B-A. It costs M-O-N-E-Y, or at least doesn’t raise as much money as a border adjustment tax would. Also, while OBA can be an elegant solution to leakage in theory, its implementation in places like the EU and California has been far from perfect. There are several industries that are probably no real threat of leakage, and therefore have no compelling argument to receive OBA benefits, that are in fact receiving a lot of allowances. But rather than fix the flaws in the system that is currently in place, the EU is embarking in a bold new direction.

If they don’t tread carefully it could backfire. I sincerely hope it doesn’t as the EU deserves much praise for continuing to push forward with one of the largest carbon markets in the world. No country, trading block, or state, is likely going to be able to sustain even modest harm to its local industries if these harms are not seen to be producing tangible benefits to the world’s climate.

James Bushnell is a Professor of Economics at the University of California at Davis and writes for the Energy Institute at Haas

Source: energypost.eu